”Here's my time in the unknown” - haastattelussa Renee Gladman

Monialainen Renee Gladman on Runokuu-festivaalin päävieraana. Yhdysvaltalaista runoilija-prosaisti-esseistiä haastatteli Lydia Lehtola. Haastattelu julkaistaan poikkeuksellisesti englanniksi, suomenkielinen juttu tulee verkkosivuillemme myöhemmin.

Lydia Lehtola: Where do you come from as a writer and artist?

Renee Gladman: I studied philosophy as an undergrad and I was really struggling with it because it didn't feel like you could freethink, you had to think through these texts that had already been written. But then I discovered poetry, where you could think your own thoughts and make your own philosophy.

I started as a poet, but a poet who was writing in sentences, because I hadn't figured out how to write my version of the novel. I was reading Henry James, Samuel Beckett, Gertrude Stein, Julio Cortázar. But my biggest influence was Leslie Scalapino. She was one of the West Coast Language poets, and she wrote poetic prose. I was really struck by her work, the way in which she would play around with narrative, and really sort of pull it apart in a poetic space.

But there is this gap between what we experience and our ability to recreate it in language.

I was interested in the breaking down of time and action. We are taught that language is for representing experience, and if you know the language and grammar you can just do it. But there is this gap between what we experience and our ability to recreate it in language. Scalapino had this beautiful way of slowing that down.

In my novels there is subject matter, and characters, places, topics, but people still call them poems because of the language. I'm not trying to tell a story as much as move around inside of one that is already happening.

”My decision to drink only fresh juice, which costs as much as a small satisfying breakfast, kept me busy rounding up cash. I would have to leave most friendships behind. As a way of keeping my life “wall-free,” I had to divide my time. I would spend the first part of the day searching for volunteer positions in organic juice factories. The second part of my day I would spend telling people about the first part. The other parts are not of substance here. ”

(from Juice, 2000)

There's 16 years between Juice and Calamities (2016) but I'm sort of the same person looking out into the world. The core questions are the same. In Juice there is a part about the apple juice crisis, and that was the first time I could feel like this is the rhythm I've been searching for, this obsessive wanting voice.

LL: You made air quotes around ”the apple juice”, is that something you would like to talk about? I read an article where someone wrote about the juice being a metaphor for capital, but i really loved how the juice could be anything.

RG: It's funny because people are reading my books around gentrification, comments on capitalism, comments on race-relations or social problems. And it's not that it isn't there, but that's never why I'm writing. I was literally obsessed with juice in '96-'97, healthy fresh-squeezed apple juice, it was just like drinking the nectar of joy. But then people in Southern California started to get sick from it, so they had to take the juice off the market. So I literally had a juice crisis, because I just couldn't get it and it changed my day.

But I can see how that could become so many different things for a reader. And I think that’s how we read. If someone said that this is a commentary on how consumerism can totally disrupt your life, it's not like it isn't there, but I'm not necessarily commenting on it. I'm just in my crisis. And not even trying to critique myself, I'm just obsessed with the juice.

As a writer, you get used to being read, and knowing you can't control what people are bringing to the text.

I think that's just what happens when people are trying to connect the text to the world around the text. And I think about things like gentrification all the time, so it makes sense that people read these novels and leap to these ways of reading. As a writer, you get used to being read, and knowing you can't control what people are bringing to the text. So I just write from where I am. The fact that there is a narrative is kind of a byproduct to my writing. I write sentences, the narrative is not the primary thing.

“I began to think there was no real evidence I was living. We all believed we were in this multiplex, though there was no way of proving it. The books said you were in a world: they told you how to accumulate worldly things; they said if you looked to your left there would be an object; they told you what you were sitting on. Suddenly, there were names that went for things that were and were not there.”

(from Calamities, 2016)

LL: You have recently made a turn towards visual poetry in Prose Architectures (2017). What is the relationship between images and writing in your work?

RG: Prose Architectures was the first time I was drawing in relation to writing. It was amazing, because it was a way to feel that I was still writing, but I didn't have to write, just move my hand. The drawing suggests a kind of dense script. I could think about the mechanics about making a narrative without having to worry about building a narrative or be responsible for anything I was saying. You can look at the drawing and see the intimacy of the hand. Something is being figured out, left open, processed. It feels like a great thing to do next to writing, so drawing is like a great companion to that.

You can look at the drawing and see the intimacy of the hand. Something is being figured out, left open, processed.

I recently wrote a series of texts that go with each drawing, and that's new for me. When that project comes out, it will be the first time that the two are together.

LL: What is making art about, to you?

RG: I'm interested in layering, seeing the different levels of something. I'm always aware of in-betweens and edges, architecturally and intellectually. I write novels that people call poems, i do drawings that people call poems. People can't help but read the inbetween-ness. I am just trying to write from where I am. I don't like to research or to know, I like to be in a place of discovery, having to make everything up. That's a funny thing to package and give to another person: here's my time in the unknown.

LL: How do you feel about people calling your novels poems?

RG: People call things poems, because poetry is the most accepting form there is. To me that's frustrating. I want fiction to learn about itself. Not that it is just a representation of reality, or that a memoir is just a recreation of what you remember. I want these poetic novels to be read as fiction. That’s my resistance. Fiction can think about silence in itself or disruption or how time doesn't always match up. And it only will do that if you create a kind of disturbance.

LL: In its history, the novel has taken many forms, sometimes experimental or all over the place. Do you feel like the definition of a novel has somehow become more narrow now?

RG: I think a lot of people go to fiction for escape or entertainment. At a certain point when they're done studying, people don't want to continue being in spaces of inquiry. They have too much to do. But a hundred years ago people were reading Virginia Woolf and James Joyce. In the US there is now more of a tolerance for works in translation. US readers can accept a weird Estonian novel, but not one written in English by a US artist.

LL: Have you felt the weight of that, the sales and readers expectations?

RG: I've never tried to be conventional. I've never had the chance to be conventional. I was born unconventional.

Most people think you can’t make a living as a writer, especially as an experimental one, but I've learned there are other ways to make money. People invite you to come to a residency for a year, or you sell a drawing or get royalties. I don't want to talk about it like it's easy. I was sort of forced to it. And all these things started falling into place. Adding a visual element to my art has really expanded the reach of my work. I hope I can go on like this forever.

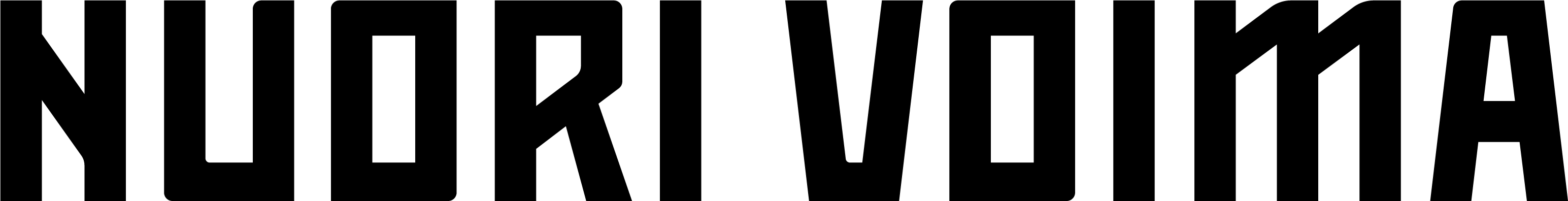

Renee Gladman (s.1971) on yhdysvaltalainen kirjailija ja taiteilija. Hän on julkaissut 14 teosta, joista tuoreimmat ovat proosateos Morelia (2019), visuaalista runoteosta lähestyvä Prose Architectures (2017) sekä genrehybiridisen Ravicka-romaanisarjan viimeinen osa Houses of Ravicka (2017), joka unenomaisessa ja filosofisessa fantastisuudessaan asettuu Jorge Luis Borgesin ja Italo Calvinon töiden rinnalle.

Gladman esiintyy Runokuu-festivaalin päätapahtumassa Poetry Mixtapessa Suvilahden Tiivistämöllä la 24.8. - eli tänään. Runokuu-festivaalia järjestää Nuoren Voiman Liitto, joka myös julkaisee Nuorta Voimaa.